Bruce Thompson

Camcloon Dairy, Ballyfin, Co. Laois, Ireland

I’m the eighth generation on my farm, a family farm. I originally studied automobile engineering, and came home to farm after my dad had lost a lot of his herd to tuberculosis (23 years ago). I decided to come home for a year and help him out with the intention of going back to my engineering career, but I never did, I fell in love with farming and have stayed at it since. I took over the farm in my own right in 2012, and with the abolition of milk quotas in 2015, we increased the herd to 300 (Jersey Friesian cross) cows, intensifying the system somewhat and concentrating on dairy (moving away from sheep and cattle). We leased farmland and bought some land as well. So that’s how we arrived to where we are today, we now have about 320 cows.

We are a grass-based dairy farm. Our key focus is on turning a non-edible grass for humans into an edible protein for humans, and we want to do that by doing as little damage to the environment as we possibly can. So, we’re looking at key efficiencies in terms of the animals – looking at kilogrammes of milk solid output relative to their body weight… It gets very technical, we are keeping a very tight rein on imports as well, trying to use as little grain as possible in their diet. We are calving to maximise the use of grassland, which has a very predictable but seasonal growth. We calve cows in a very tight compact season so fertility in the animals is very important as well. We’re then rearing our young stock in a way that trains them to manage parasites and pasture themselves – encouraging their own immune systems to be able to fend off parasites. This learning how to manage them when they’re younger means that as time goes on, they don’t then need to be wormed, so it’s reducing the amount of pesticides that need to be used.

I had always been interested in soil but began to explore the relationship between soil and animal health more and developed an interest in anthelmintic resistance and how we could control that biologically, or rather manage parasites better biologically. I started looking at dung beetles and the effects that the anthelmintics (by which I mean wormers and insecticides) had on biodiversity, and how we could reduce those and increase biodiversity on the farm using dung beetles and insects.

I applied for a Nuffield Scholarship and did a lot of travelling and research for it all over the world, starting at the end of 2019, and into 2020. Then COVID made a mess of it! I suppose that had its negatives and positives – it meant that I could reach a lot of people quickly; for the first half of 2020, if you wanted to talk to someone for 10 minutes on Teams or Zoom, there was no problem because they were all at home bored! I began travelling in 2020 down south Australia and Tasmania and got to finish the travelling in 2022 when we were allowed to travel around again. I got invited onto the COWS working group in 2022, and the technical working group for parasite management that’s part of Animal Health Ireland. Last year, I completed a diploma in Sustainable Farming and the Environment in University College Cork.

From an Irish context, 91% of dairy produce is exported, so my consumer is not necessarily next door to me, but rather in Asia, Africa or America… This has its pros and cons. The pros are I don’t get to sell the produce to my neighbours, so I’m not dealing with marketing. The cons are I don’t get to sell the produce to my neighbours, so don’t get to see our end consumer. From an industry point of view, that has bitten us a bit because we’ve taken our neighbours for granted somewhat. If we went back 50-60 years ago, there were a lot of people involved in agriculture and food production, you could go on to any farm and there was nearly as many people as there were animals on it. Now, with efficiencies and people becoming more urbanised to an extent, we are likely to have people living beside us that we don’t really know, and they don’t understand what’s happening on the farms.

We’ve tried to buck that trend a bit here and get people interested. We have farm tours, sometimes school tours. With the Farming for Nature Ambassadorship, we have open days on the farm. We try to encourage people who are not connected with agriculture to go on to the farm as much as possible. However, it’s not like they’re going to go up to the shop up the road and buy Bruce’s cheese because Bruce doesn’t have cheese and Bruce’s milk ends up in formula in China…! So there are pros and cons, but we recognise that marketing is not something we should turn our back on, and we’re very far away from our consumer. When the public actually meet people that are producing produce, they become more interested and realise that we do take a lot of pride in what we’re producing. Opening up your environment for people to come and have a look and find out about things also helps people to feel more connected to the environment, which is really important because there’s such a disconnect these days. Provenance of food I think is also very important, and people increasingly realise the most efficient places to grow products are from an environmental point of view the best ways of doing it.

Sustainability in practice

Managing hedgerows for biodiversity, and water and slurry management

We haven’t topped our hedgerows for a number of years now – since we realised there there’s more of a potential positive input to ecology to not cut them and leave room for nature. We’re planting hedgerows as well (probably about a couple of kilometres every year), planting anywhere we think we can work them into the farming system… We’re also planting trees in the middle of fields. We’re using cactus tree guards for protecting the trees. The hard part about planting a tree in a field is keeping livestock away from it, so the guards are making it much easier and cheaper, they are easy to put up.

My fertiliser spreader is nearly as old as my dad, it doesn’t have GPS on it! We’ve planted trees within fields at the spacings we need for driving the spreader, we literally drive from one tree to the other, using them as markers on the farm. We purchased some forestry on the farm to provide firewood, including heating my own house. So we do cut down trees, but the planting kind of negates it and helps offset some of the carbon lost. I’ve done a good bit of travel as well, so it also helps alleviate some of the guilt in relation to that!

I like to plant trees and don’t see why we shouldn’t. I like the Japanese philosophy of true society being where men plant trees that they never sit under the shade of. At the end of the day, when I’m gone from here, all I’ll leave behind me is my memories… it’s not going to be how much I have improved the wealth of the farm or the value of my business, it’ll be memories, and things like trees are a reasonably long-lasting thing to put on the landscape. They also look good and have got good biodiversity connotations.

We also have integrated two wildlife ponds into the farm. One of them is building on where there is a constant flow of water all year round – it was an easy one to put in and is quite large. The other one has been put in because I need clean water coming off the farm, so water off sheds in yards goes through this other pond and ensures that the water coming out of the farm is 100% clean. We have plants and fish in it so the proof is there…

We’re on low emissions with spreading slurry and using trailing shoe as opposed to splash plating, so there are less gaseous emissions from that, and we’re working at ensuring an optimum pH in the soil.

We put up some bird boxes around the farm and I’ve mass reared insects (the dung beetles) and let them out on to the farm as well – both in fields enclosures and in an incubator in the workshop and the farm as well.

Incorporating multi species swards into grassland

We incorporate multi species swards with all grassland that we reseed now. Initially I started using white clover, perennial ryegrass and chicory. My thinking at the time was the soil here can be quite heavy and shallow. I saw practices in New Zealand where they were planting monocultures of chicory to burst open the subsoil. They would then decimate it after 12 months and sow perennial ryegrass into it, but the taproot, that goes down (a metre into the ground easily) stayed there. We found that encouraging perennial rye grass roots created more natural nitrogen (N) through mineralisation as a chemical, so it reduced our chemical N input.

Moving on from that, we started incorporating red clover into the mixes because red clover again fixes N through rhizobium nodules in the roots in year one, (whereas with white clover it is year 2 before it starts doing this). However red clover doesn’t persist with livestock grazing because it doesn’t like being trampled, the growing point is quite high on it. We’ve used plantain more latterly. It has a longer growing window and is more persistent (from what I’ve seen so far); what I’ve planted is still present. We have found that chicory dies off after a couple of years, plantain seems to continue growing. It also is a diuretic.

A lot of the issues with nitrate and waterways is stemming from urine from cows, from stocking farms. The parts per million of nitrate in the urine can be very variable, so the more stock you put in and the more protein you put in their diet, the more concentrated with nitrate those urine particles are going to be. Two areas we’re focusing on is making sure there isn’t a high flush of a luxury uptake of N into the grass sward, so the cows don’t end up with a lot of protein in their diet that they end up turning back into nitrate and peeing out. To do that, we have to spread little and often and we’re using protected urea which is slower as it has inhibited release in it, so cows get a lower protein input from the grass sward. The plantain in the mix then helps water percolate down and the club root that comes out of the plantain captures a lot of the nitrate and keeps it in the sward, so we’re not actually losing it as such. It’s a much more efficient use of N – natural and chemical.

The Timothy we’re putting in is more persistent in heavy types of soil, it grows at lower temperatures and it’s a bit more fibrous, so it gives the cows something to chew on in the spring and autumn when grass can be quite soft. We’re using more diploid grass swards in heavier wetter types of fields, and more tetraploids in the dryer ones. There are always both, but the ratio of them changes. We have a bit of yarrow in the mixes as well – there isn’t much feed value in it but we include it for biodiversity reasons.

Using dung beetles to manage parasites

The biggest threat to the dung beetle is habitat loss and that habitat is dung pats. We need dung pats! The second biggest threat is not having the right dung pats. They need to be clear of antiparasitic because they are absolutely detrimental to the populations of dung beetles. So the question is how to manage that without giving animals wormers? One of the answers to that is provided by the dung beetles themselves, because they kill the parasites. How that works is dung beetles like a stiffer type of dung pat – for that, the mixed species swards with stemmier grasses are better. Dairy cows tend to have looser dung pats irrespective of what you feed them – when they’re lactating, they put more water through the system and produce a more liquidous type of dung. It’s not always what you’re feeding them either, it’s also what they’re doing…

The dung beetles come into the dung pats which are lovely little incubators to hatch parasites. The pats are moist, full of carbon, warm, sheltered, and still. If you were in a lab trying to hatch parasites, you would have a dung pat that you would keep moist, you would keep the sunlight off it, and you would leave it perfectly still and untouched… Dung beetles disrupt all of that, they start moving around in it, they dry it out, turn it over, and bury it in the soil, which ultimately means eggs can’t get out on to the pasture.

This messes up the lifecycle of the parasites. Lungworm also uses a fungus called pilobolus. It waits until the weather conditions are right and then this fungus that has a little black top on it appears. It is not harmful, but it spreads when the weather conditions are correct (it’s reputed to be the fastest living organism). Lungworm swims up the stem of this fungus on to the tip, and when the tip explodes, it catapults it out onto the grass, ready to infect the animals. Again, it needs the right growing conditions; it doesn’t want moisture or the dung pat to be disturbed, both of which the dung beetle can mess up.

Grazing management

The lungworm parasite pops out onto the grass. The other parasites swim out and climb up the stem of the grass, but they like it to be moist and they don’t like it too hot (which it is lower down in the sward). Grazing up high is therefore beneficial, and grazing off the top also lets more light into the bottom, which helps essentially ‘cook’ the parasites, which is important.

Reducing the antiparasitics is key to ensuring that we have plenty of dung beetles on the farm, so we do that by encouraging this higher grazing of the sward, which reduces the amount that the cattle ingest because we want to interrupt the parasites’ life cycle. We have found that the best way to do that is to give the cows as long as possible out of pasture, therefore the parasites die off before the animals have a chance to ingest them. We want to make sure that the most susceptible animals don’t pick them up – that’s where grazing high with our calves comes in and putting them on to the pasture that is least contaminated. The young stock are most susceptible and they also produce the most amount of eggs in their stomach, so when we graze a pasture with our young stock, we want to avoid grazing it again particularly within 6 months. We definitely don’t want to be rotating the same group of animals around the farm.

Faecal egg counting

We send off samples to labs to see if there are any eggs coming out of our animals because more often than not there isn’t, particularly in the first half of the season. There is a tendency to overestimate the amount of parasites that are coming out of animals and the amount that animals actually need to be wormed. They don’t need to be wormed that much at all. To put some figures on it, approximately 90% of the parasites on a farm are found out in pasture, and 10% are in the animals at any one given time. When you talk to a farmer about parasite control, they’ll generally say “well I worm my animals at this time, that time…” But they’re only talking about the 10%. We need to rethink it and concentrate on the 90% – which is where grassland management becomes very important. 80% of the parasites are in 20% of the animals. So we need to focus on the 20% of animals.

This is why we do faecal egg counting and we have a threshold – it changes at different times, but it is about 250 eggs per gramme (EPG). If my calves go over 250 EPG, and I get a sample back at 300 EPG, I would then decide to worm them. We put them onto weighing scales, and calves that have not hit their expected weight gain are wormed, but just those ones. We have to focus on the 20% and maybe they need to be wormed more often than we thought, but we need to use less wormer overall because if we were to faecal egg count every single calf in a group, the majority of them would come up with 0, but the odd calf will come with 2000. It’s important to get that 2000 EPG calf and worm them because they’re contaminating pasture, putting eggs back out. It’s what we call a targeted selective treatment and the best analogy I have is selective dry cow treatment when it comes to antibiotics – the basics are the same. Our cows need a clean environment so that they don’t get mastitis. We check our milk tank to see what our cell count level is. If it goes high, we look for the culprits in the herd and we give them antibiotics. It’s the same principles with targeted treatment with wormers – we keep our environment clean (our pasture), we keep checking out faecal egg counts to see what the level is, and if it goes high, we find the culprits and we treat them.

This is the simplest way of putting it – to dairy farmers in particular! We have been very targeted with our use of wormers and it’s amazing how little wormers we actually need, but the difference it makes to a group of animals when you can find the culprits is incredible – and it’s always the same ones – there are animals in our herd that have never seen a wormer in their life, even though we manage it very conventionally. If you think about it logically, if animals are putting on body condition, what are we worming them for?

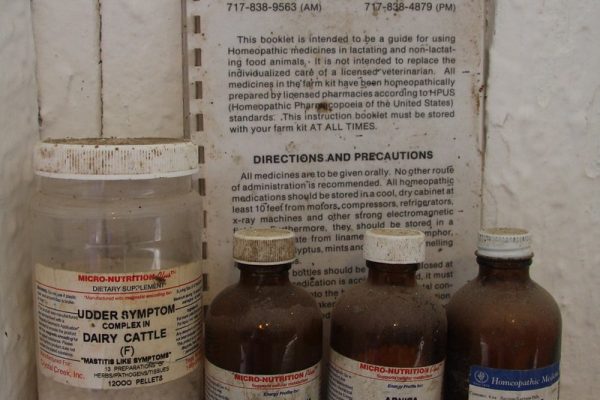

Antiparasitics

One of my motivations behind it all is looking at it is anthelmintic resistance, which is the same as antimicrobial resistance. I actually think we’re going to hear more about it over the next couple of years – I think it’s very widespread. Teagasc conducted a trial back in 2018 – it’s becoming a bit outdated now, but at the time they tested 24 farms for antiparasitic resistance. 24 of them had resistance to it. So that basically means that the products are probably working at half their efficacy. So we have to start looking at things differently. Recently, our Minister for Agriculture signed into law that the antiparasitics now have to be prescribed by a veterinary practitioner. It caused uproar, but it needed to be done.

The other antiparasitics that we use are the fly control products that we put on the animal backs. We never really use a huge amount of them, but I suppose the big threat is our in-calf heifers. We play the weather conditions in front of us -if we’re seeing a lot of flies, we’ll bring the heifers in and we’ll put Stockholm tar on to their teats, we haven’t used fly control products. And we use eucalyptus oil in the teat spray for our dairy cows. With the stock going into sheds, we shave their spine with a haircut and we use ground limestone along the spine. That stops the lice from hatching or from trying to lay legs, it works pretty well.

Breeding dung beetles

We’re very lucky here because in this part of the world, dung beetles are already on our farms, we just need to increase their populations. The problem is that if there isn’t a lot of competition for food or for a mate, they don’t work as hard. If you put them into a small, enclosed area and feed them a small amount of feed, they perceive that it’s a threat to their population, so they will fight over each other. The females lay more eggs, and they will work a lot harder to try and reproduce at a higher rate. The opposite happens if we use a lot of wormers in our animals – it cuts down the numbers of them and means there are only a small number in the dung pats, they don’t work as hard, so don’t multiply at the same rate at all. What we need to do is basically create a locus-like effect – to get a swarm of dung beetles, putting them in a small enclosure and feeding them the right amount of feed. The beetles we have on the farm are all native species, so we largely use them to breed from. The most successful are the ones that are captured on the farm.

I have caught some down in Carlo, I had to get permission to do that from the Department of Agriculture and put them in an incubator in my workshop here (see below), it was temperature controlled because there this particular species was a big up burrowing one. I basically tried to fool them that it was always August inside this environment to produce. It needs a lot more work, to be honest! But the ones out in the field have worked quite well.

I did work with the RSPB on the Isle of Islay – it was one of the Covid projects and I haven’t actually been out to see it yet. I built equipment and sent over information for them on how to do it because the species they were focusing on lay eggs just underneath the dung pat on top of the soil, and the chough bird came in and ate the larvae. The problem was the farmers over there have been using a lot of synthetic pyrotides and fleucosides in their cattle and sheep, and it really dropped the numbers so the fledglings weren’t getting enough feed. The great thing about it was because they had a bit of funding behind them they were able to calculate what the multiplication rate was through an entomologist – every dung beetle we caught, we got 20 young ones out of it.

Finances

- We’re saving about €3000 a year on product usage.

- Our savings on labour is probably negated with weighing animals more. We have to work around it with less, but we have to weigh them more, so that’s on a par. We are getting better performance from the animals because we’re weighing them more. We’re watching the lighter ones and focusing on them and getting them up to target weight because we very often separate them. We have a very tight carving pattern. Our heifers have to calve at 2 years of age, not 28 months when they’re too old and they’ve missed the window. But we have no control set, so it is very hard to put a figure on it financially. Animal performance is much better because we haven’t wormed our cows much, I won’t say at all because there is the odd one or two we do worm – but it hasn’t affected performance. They’ve increased with their output in relation to their genetic improvement.

- Maybe in 10 years’ time in comparison to what other farmers might be losing in animal performance because they have resistance on the farm, I would suggest that I might be far better off.

Motivations

The main drivers for what I do are biodiversity, animal health, sustainability… I know everyone uses that word nowadays, but I’ve kids here and I would like to think, knowing what I know, that I do the best that I can to encourage sustainability so they can see at least that I’ve set the right example, and it gives them the best opportunities going forward. It’s also about reducing our negative impact on the environment as best I can. I’m not going to be a turkey denying Christmas – food production does have a negative impact on the environment – but you can offset it in different ways, so it’s getting that balance right I think that we need to aim at.

I also just like to do things differently; I like looking at new things and areas that people haven’t looked at and trying to simplify something that’s very complex as best I can – which I can sometimes make an awful bad job of! I enjoy working with people that very often have opposing motives…. environmentalists, entomologists, parasitologists, the veterinary profession, farmers, and chemical or medical companies… I’ve worked with and got on well with all of them. But if you put them all in one room and start talking about parasite management, it generally speaking ends up with a few angry faces! I love the challenge though of being able to come up with workable solutions for them all.

I take inspiration from a lot of people: A vet called Tommy Heffernan, or ‘Tommy, the Vet’ as he’s known here in Ireland; the Farming for Nature network (I love this diverse network of people); Matt Ryan, a dairy advisor who’s very progressive, thinking ahead the whole time, Sally Ann Spence, Claire Whittle…

As far as kind of future goals go, I’d like to connect more with the public and to enable more knowledge and demand transfer between the consumer and the farmer. Consumers think they need to educate farmers and farmers that think they need to educate consumers, but maybe there’s a bit both ways that we need to work on, because we’re a generation further away from our food source now than we were maybe 20 or 30 years ago…I think there needs to be better collaboration with businesses or direct consumers perhaps helping farmers out, physically and financially improving the effect that they have on ecology. We’re trying to commoditise our products too much; I think we need to maybe put a price on nature. I don’t believe consumers as against us as much as some may think. They want farmers to be successful, they don’t want the countryside wrecked. Simple as that.

I’d like to focus on building on some of the small research findings from the farm, so that they could be enacted on a larger scale on farms. We have developed grazing strategies that seem to have worked here, I’d like to see them trialled on a larger scale. Targeted selective treatments are definitely working so I think that our grazing strategies could work as well.

Farmer tips

- Reducing worming – A vet absolutely needs to be on top of things, so talk to the vet and explain to them that you want to reduce the amount of wormers being used on the farm, explain why, and ask them to come up with a workable targeted selective treatment, or more holistic parasite management.

- Monitor insect populations – Go out to your pasture, shovel up a nice, stiff dung part and drop it into half a bucket of water and see what floats out of it. If you give it a bit of a mix, the insects will float to the top – just in that one dung pat, look at how many insects are in it.

It’s important to note that a lot of the biodiversity loss, particularly with birds, is due to food shortage rather than habitat. We could put up lots of bird boxes and do everything right with hedges, but if there’s no food it’s just not going to cut the cheese! So we need to look at these insects as a food source.

Bruce was instrumental in helping set up Dung Beetles for Famers, a group of farmers, entomologists and a vet, whose aim is to inform farmers and vets of the importance of these insects on farms.

Also see ‘Ask the Farmer Q&A with Bruce Thompson‘ – Courtesy of Farming for Nature.

All images and video clip courtesy of Bruce Thompson