Black-grass: what’s the problem, what’s the solution?

Although often considered a relatively ‘new’ weed, it was recognised as a ‘very troublesome weed among wheat’ over 175 years ago (Sinclair, 1838). However, black-grass has certainly become more widespread and more problematic to control during the last 50 years. Why is this?

The problem

The three principle reasons for increasing problems with black-grass are:

1. More crops sown in autumn, especially winter cereals and oilseed rape. In 2018, about 66% of arable crops (mainly cereals and oilseed rape) were sown in autumn. Why is this relevant? Because 80% of black-grass plants emerge in Sept/Oct so, sowing at this time results in a higher proportion of black-grass emerging within the crop rather than before sowing, when destruction is easier.

2. A trend towards sowing crops earlier in the autumn. In the mid-1970’s, less than 5% of winter wheat crops were sown in September whereas, more recently, over 40% – 50% of crops were sown in September. The trend to ever-earlier autumn sowing exacerbates the black-grass problem.

3. Herbicide resistance. The two factors above would be of no consequence if herbicides could be relied upon to kill black-grass effectively. Unfortunately, resistant populations now occur on most of the 20,000 farms where herbicides are applied regularly. Not only is resistance widespread, but it also affects most herbicides. Forty-one herbicides have been introduced for black-grass control during the last 60 years and resistance now occurs to nearly all of them.

The solution

It is now widely recognised that diversity is the key to successful long-term black-grass management with greater use of non-chemical methods of control and less reliance on herbicides. An integrated weed management (IWM) approach is needed, in which as many tactics as possible are used to combat weeds.

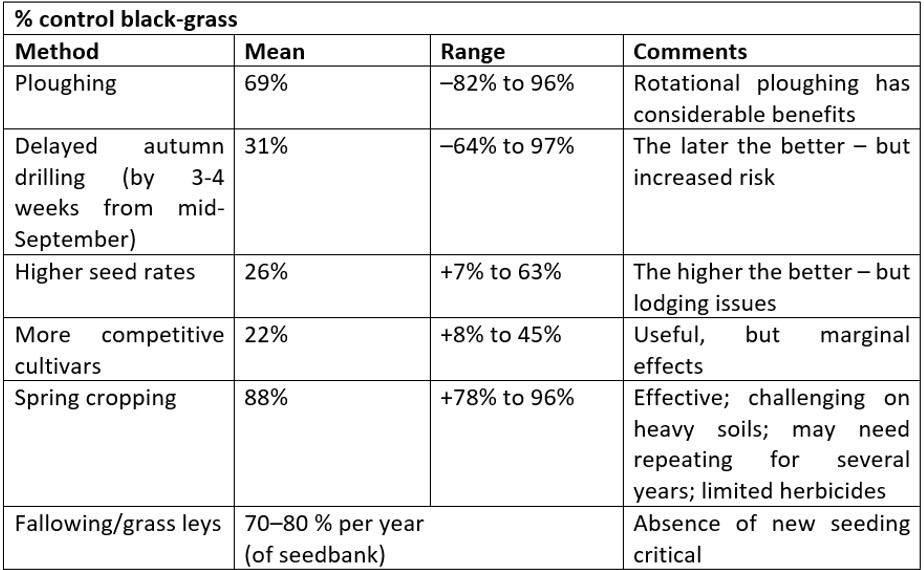

Many non-chemical methods of control are available and the table below quantifies the effectiveness of the main methods for control of black-grass in winter cereals based on a comprehensive review of over 50 field experiments (Lutman et al., 2013).

The modest and variable levels of control for each method highlights why it has been so hard to get farmers to adopt alternatives to herbicides. The costs, risks and inconvenience of alternatives are immediate, yet the benefits may take a long time to become apparent and are less predictable. Consequently, farmers are tempted to delay adoption of alternatives – herbicides are seen as the easier option. Or, more accurately, ‘were’ seen as the easier options. Widespread resistance combined with a lack of new herbicides mean that most farmers are, out of necessity, now adopting IWM. The aim must be to integrate the use of many non-chemical control methods, in combination with herbicides where necessary, to improve overall control.

The ‘5 for 5’ initiative

This aims to encourage farmers to adopt comprehensive strategies to tackle black-grass by maintaining a planned, integrated approach at the individual field level for at least five years. Why five years? Because this is how long it takes to reduce the black-grass seed burden in the soil substantially, providing new seed production is minimised. The relatively short seed persistence of black-grass (about 74% annual decline in seedbank) is its one weakness – ‘5 for 5’ aims to exploit this.

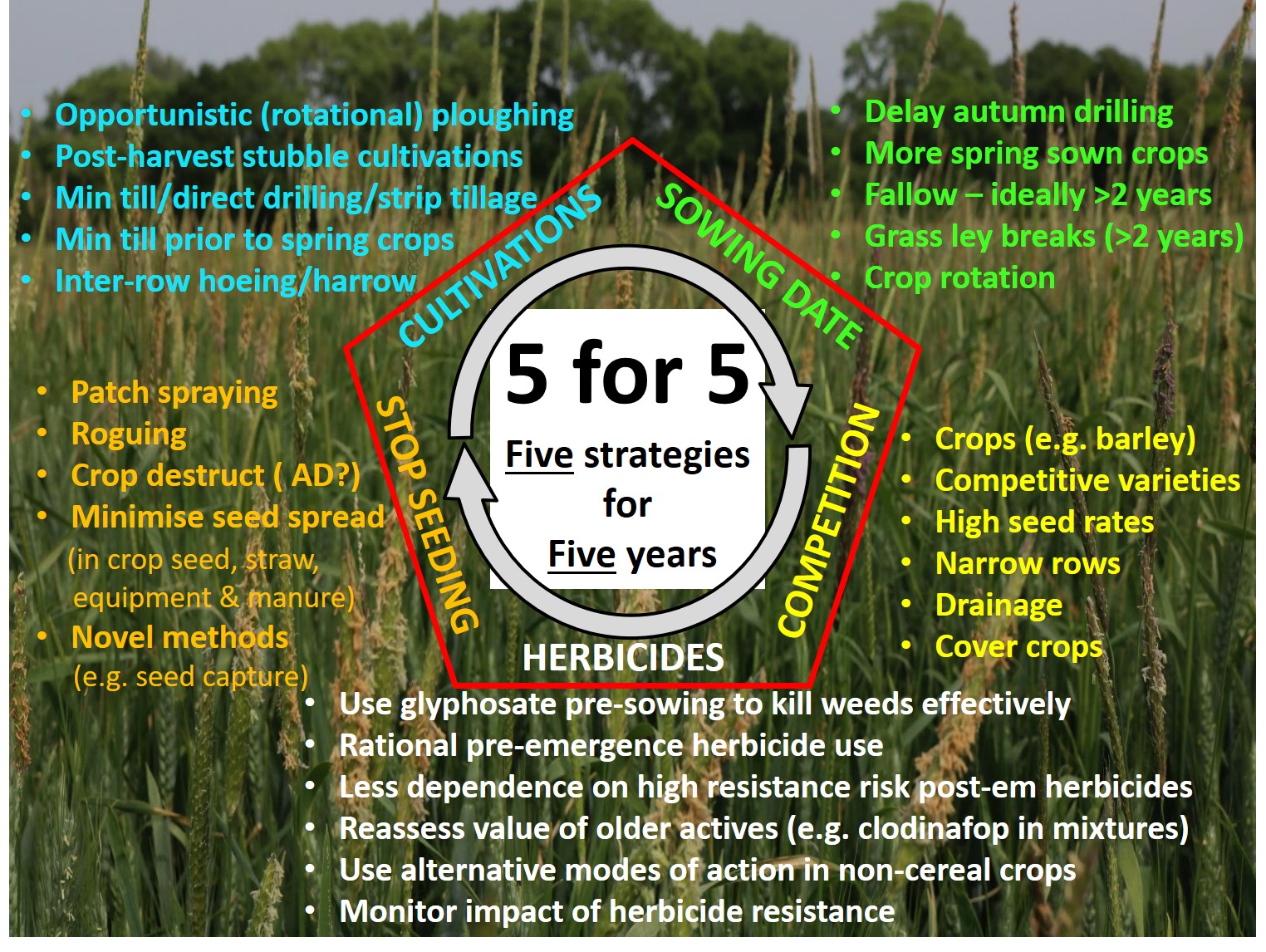

Farmers are encouraged to plan a strategy for each field involving all five of the main components shown in the diagram.

There is no single ‘best’ blueprint – the most appropriate strategy will vary from field to field. Farmers are also encouraged to: Record the amount of black-grass, and its location, in every individual field to quantify progress; Review progress annually to identify the most effective strategies; Revise the plan if necessary, but not to expect dramatic improvements within only 1 or 2 years.

In essence, 5 for 5 is all about: refining existing control strategies rather than relying on unproven new ‘gimmicks’; recognising that beating black-grass requires a multi-year commitment at the individual field level; and being more proactive and disciplined in tackling black-grass.

Further information: all the below are available on the WRAG website

- Black-grass – everything you really wanted to know (4-page leaflet)

- Black-grass: the potential of non-chemical control (4-page leaflet)

- ‘5 for 5’ to beat black-grass (2-page leaflet)

- Black-grass (Alopecurus myosuroides): why has this weed become such a problem in western Europe and what are the solutions? (6-page paper from Outlooks on Pest Management – Oct 2017)

Stephen Moss (of Stephen Moss Consulting) recently retired from Rothamsted Research after 40 years of studying weed agro-ecology, herbicide resistance, non-chemical control methods and Integrated Weed Management. He wrote or contributed to 251 research publications and over 350 popular articles during his career.

All images courtesy of Stephen Moss. All Rights Reserved