Fibreshed – reconnecting fashion to fibres and farming for a homegrown wardrobe

Why do we eat lamb, throw away wool and wear plastic? Why are food and fibre systems not generally considered within the same systems and conversations? When they are, why are fibres generally only considered by-products of food production?

One answer is historical. After the last World War agricultural policy prioritised food production, leading to increased genetic selection for food yields – meat if we’re talking about sheep, or seed if we’re talking about flax – to the detriment of fibre commodities. Where once we had dual-purpose utility breeds and varieties that yielded multiple products for domestic and local use through resourceful, decentralised processing, now we work mostly with breeds, varieties and landscapes that have been ‘improved’ over the last 70 years to do one thing really well – usually meat.

Questions of breed resilience and robustness aside, as well as the detrimental eco-systemic effects of large-scale intensive farming that such policy incentivised, it is no bad thing for a nation to have security in its domestic food production – particularly at times of crisis or vulnerability. Unfortunately a similar concern for our natural fibre industry fell by the wayside, in part facilitated by the widespread introduction of synthetic, petroleum-derived fibres that happened around the same time, as well as the offshoring of much of our industry to take advantage of cheaper materials and labour found elsewhere.

Eat my shorts

I like to think that food leads the way in alternative agricultural thinking because we have such a direct relationship with it; we choose what to eat multiple times a day and what to buy to eat maybe multiple times each week. Ultimately we put that food into our mouths and assimilate it into our bodies. Most people don’t need to make such decisions about their clothing quite so frequently, nor do we ingest our clothes (!) but it’s worth remembering that we wear our clothing on our skin – the largest organ in our body and a semi-permeable membrane that protects our internal selves from the stresses and toxicities of our external environment; our clothing is our ‘second skin.’

Where we are now

In the last decade I’ve witnessed a significant shift in thinking about how our clothes are made, with much greater consideration given to provenance and the nature of the materials that we choose to surround ourselves with. The tragic Rana Plaza disaster, and the awareness raising initiatives that followed, for example – the True Cost movie, and Fashion Revolution’s ‘Who made my clothes’ campaign – have led the industry to question the social inequities of our existing clothing industry, as well as the environmental ones. If this was an emerging movement starting to gain momentum, then events of the past year have certainly accelerated it. Climate protests, Extinction Rebellion, Covid-19 and Black Lives Matter have brought into sharp focus problems arising from our dependence on the global, industrialised economy. After decades of toxic industrial agriculture and exploitative land and labour practices, people are recognising the need for change. Consumer surveys conducted during the pandemic have confirmed this, demonstrating consumers to have renewed value for sustainably made, locally sourced products, including clothing.

Fibreshed

There is now an emerging and growing movement of organisations, certification initiatives, activists and producers who are propelling this conversation ever more in to the mainstream. Central in this movement is Fibershed. Borne out of Rebecca Burgess’ quest in 2010 to produce a wardrobe of clothes from within her local ‘fibershed’1, an area with a 150 mile radius in California, Fibershed has grown into a non-profit initiative inspiring affiliate projects across the world whose objective is to increase the capacity of communities to produce clothing regeneratively within their own bioregional systems.

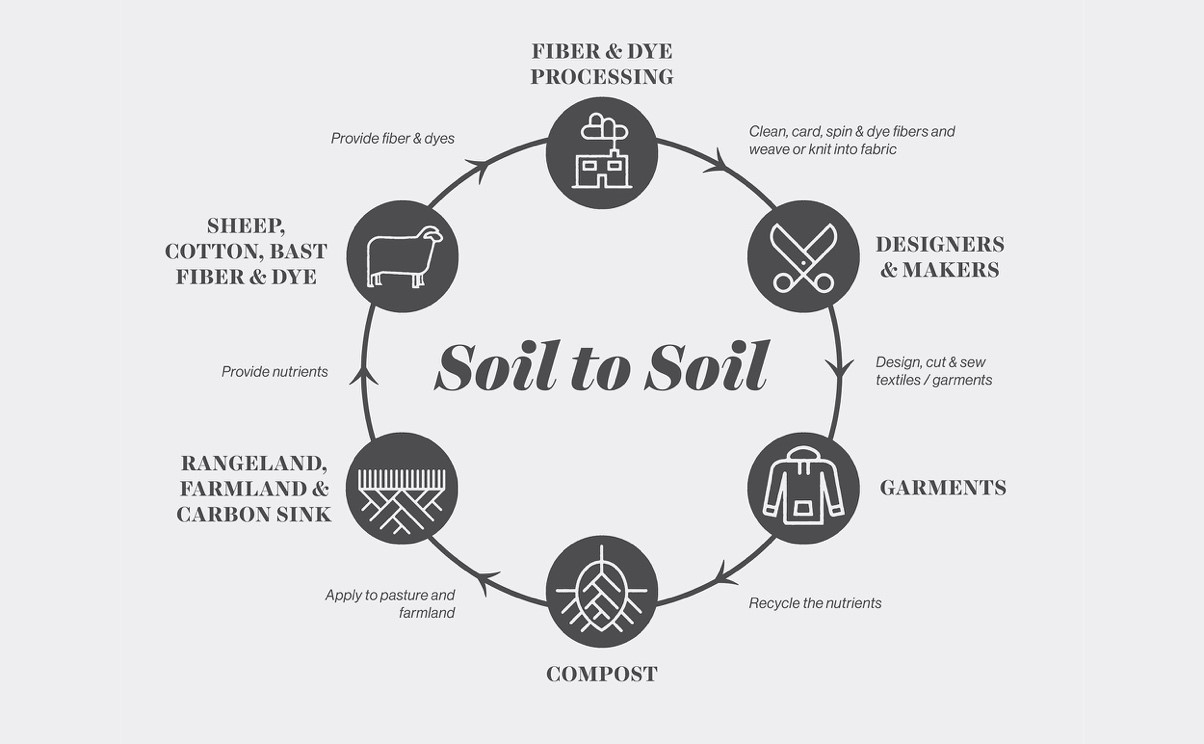

More than that, Fibershed is connected and holistic in its thinking; it offers a model that allows food and fibre systems to be considered together rather than siloed, and holds soil health at its heart. By integrating grazing animals into an arable system, soil can be improved over time, carbon can be sequestered and we can have regenerative farming systems that provide meat and dairy as well as animal fibres, cellulose fibres and natural dyes. For me, what places Fibreshed at the forefront of new systems thinking, is that it reconnects fashion to fibres and farming, and therefore also to our environment – a connection that we lost long ago in the UK.

I see the fibershed model as the circular economy model, that positively contributes to economic, social and natural capital by using Nature’s own ecological processes. Beginning and ending with soil it closes the loop without the need for additional chemical, technological or energy inputs.

The challenge

Mine and others’ research with fibre farmers, mills, designers and brands of all sizes has demonstrated that there is increased industry interest in, and demand for, natural fibres for clothing production.

Fernhill Farm, Somerset

Likewise, there is enthusiasm and willingness among growers to try new and novel crops – dye plants, or flax and hemp for fibres, for example, particularly where they can be used within a crop rotation plan to build and regenerate soil health. More shepherds would consider keeping dual purpose sheep breeds if they knew they could get a decent price for the fleece. More designers would work with small farmers if it were easier and faster to process into quality-consistent yarns and fabrics. What is missing are the facts and figures required to reassure all levels of the supply chain that both the demand and the production capacity exists, and to understand what is required in terms of processing infrastructure to ensure a desirable, consistent and quality material can be produced.

For this is where our biggest challenge lies. Our wool processing capacity is now very limited, and commercial cellulose fibre processing specifically for end-use in garments is non-existent. My outreach with potential research partners beyond the textile and fashion sphere has illuminated the parallels between our obstacles and those in other agricultural sectors. For example, our UK grain and flour industry has a similar bottleneck around milling and processing, leading to exploration of alternative, decentralised and community or farmer-owned models for processing – as discussed by the UK Grain Lab.

Call to action

I, together with our wider Fibershed community and a diverse group of industry stakeholders nationwide, see a pressing need to facilitate a robust scoping study that will provide the missing data as well as create a strategic jumping off point for informing potential investors, future policy and industry development. What we are hearing is that this could be interesting not only as a fibre and textile project, but as part of a wider project that examines the value of developing more integrated, holistic, ‘mosaic’ type agricultural systems for farming both food and fibres. In turn these would necessitate more regional, decentralised facilities for processing and distribution that support producers in capturing maximum gain from their crops, while offering customers increased traceability as well as the intangible benefits that come from connecting and consuming products from their own, local landscapes.

We are actively fundraising to commission this study on a national scale and are calling out to funding and research partners, as well as fibre and dye growing partners on the ground who want to be part of this conversation going forward and who are willing to collaborate in seeing this come to fruition.

- Contact me at hello@southwestenglandfibreshed.co.uk

- Fibreshed UK Instagram

- South West England Fibreshed Instagram / Website http://www.southwestenglandfibreshed.co.uk/

- South East England Fibreshed Instagram

Emma Hague says of herself:

“When put on the spot I call myself a researcher and project manager, although this belies the variety of work I’ve been involved with since I graduated with a BSc in Anthropology in 2006. I spent 5 years working with fibre growers and textile artisans in Peru to build a vertically integrated textile and fashion system with a grassroots organisation I co-founded, called Awamaki. Since then I’ve worked on similar micro-local initiatives here in the UK, founding Bristol Textile Quarter, South West England Fibreshed and co-founding the Bristol Cloth. At the other extreme, I’ve also spent three years working at a global level on sustainable natural resource development with specific expertise in indigenous peoples’ rights and community engagement. Rural economy, natural resources, community empowerment and sustainable supply chains are the common threads which tie together all the projects in my portfolio, as well as marrying my personal interests in alternative economy, agroecology, artisan crafts, gardening and food. I now live with my partner on a smallholding in Gloucestershire, embarking on a steep learning curve to steward it back to a productive smallholding, accompanied by a growing herd of Golden Guernsey goats.”

1 Interpret same as you would ‘watershed’

Header image shows grading a Shetland fleece, Fernhill Farm. Credit for images: Alex Ingram, Bristol Textile Quarter