Groundswell 2019: Farming with Nature to produce healthy land, people and profits

Inspirational. Innovative. The best farming conference in the UK. These are just a few snippets from recent Twitter posts describing Groundswell 2019 – but are they true? In my opinion from attending the second day, the short answer is a resounding “YES.” But why is it so good?

Groundswell is the brain-child of the Cherry family and held on their Hertfordshire farm at the end of June. “Run by farmers, for farmers,” it combines a mix of theory and practical sessions for anyone (not just farmers) interested in improving soil health and working with nature to grow food profitably. Now in its fourth year, the theme for this year’s Groundswell event was ‘Conservation Agriculture: Practical ideas on how to farm in the new environmental and political climate whilst regenerating your core asset – the soil.’

The two days consisted of a mix of workshops, demonstrations, seminars, panel discussions, interviews and exhibitors – with up to six different sessions running in parallel at any time. It is a testament to the Cherry family’s extraordinary organisational ability that the event ran so smoothly. Furthermore, they also managed to attract internationally renowned speakers who discussed practical ways to improve soil health, mitigate flooding and sequester carbon.

But the event was much more than this. As I meandered around the site watching the direct drill demonstration on the field opposite, there was a feeling of good will, a buzz of enthusiasm and a palpable positive energy for change. Folk I’ve never met, or only know through social media, were eager and willing to discuss their farming systems, soil properties, water management and marketing ideas.

Being spoilt for choice and despite being billed primarily as a no-till event, I decided in advance to focus on sessions that seemed relevant to livestock management. So, I knew I wanted to start the day listening to Allan Savory (Holistic Management pioneer) and end it with Charles Massy (author of ‘Call of the Reed Warbler’) – even if it meant getting up at 4 am so that I could ‘do’ my animals and still beat the traffic down the M1.

Both emphasised that agriculture is the basis of civilisation. However, ever since the plough was invented over 10,000 years ago, farmers have fought with natural processes to grow food. This misguided policy to control, to simplify and, when “necessary,” to kill has led to massive soil loss across the globe. In the last 60 years, modern industrial agriculture has accelerated world-wide soil destruction through over-grazing, over clearing, over burning and industrial cropping (with its use of monocultures, pesticides and synthetic fertilisers). In the process, soil microbial life has been decimated, the small water cycles have been disrupted and six of the key biophysical earth systems (climate control, biodiversity, land-system use, fresh water use, biochemical phosphorous & nitrogen flow) have been destabilised.

But despite this gloom, both Savory and Massy explained that the solution is pretty simple – regenerative agriculture which produces healthy landscapes that are truly diverse and functional. These will generate healthy food and fibre which in turn results in healthy people and a healthy planet. Moreover, farming with Nature rather than fighting against her can be highly profitable because not only are the huge industrial and chemical costs eliminated but, when done effectively, the yield also often improves. So perhaps it’s not surprising that farmers of all ages and from all parts of the UK are starting to enthuse about the possibilities and come to Groundswell to learn more.

Although every farm is different, if you want to improve the soil, there are several basic principles to aim for: keep the soil covered, reduce soil disturbance and increase plant density and diversity by incorporating deep rooting cover crops into crop rotations or into permanent pasture. This not only protects the soil, but it also enhances the amount of photosynthesis. The plants then respond by pumping out sugars and other exudates from their roots which feed the soil and increase the soil biology (and soil carbon).

These actions also help make any rainfall more effective. A spongy, healthy soil under permanent pasture is especially good at absorbing water and holding onto its nutrients. A fact that was clearly demonstrated by Jay Fuhrer, a soil health specialist from NRCS, using a rain simulator. The result of this improved water utilisation is that the land becomes more resilient to drought and less likely to flood.

Plants, animals and soils evolved together and all the speakers I listened to emphasised that grazing livestock should be an essential part of the natural equilibrium. However, because of unwise government policies and/or a lack of understanding about landscape ecosystems and soil biology, animals are too often either completely removed or else confined within a single area for too long. In this second case, they will almost inevitably overgraze the site plus destroy the soil structure with their hooves.

I heard two different approaches for including livestock while farming regeneratively and working with Nature. In one, Isabella Tree described how low-density livestock (pigs, cattle, ponies and deer) act as the drivers for change on the 3,500 acre Knepp rewilding project.

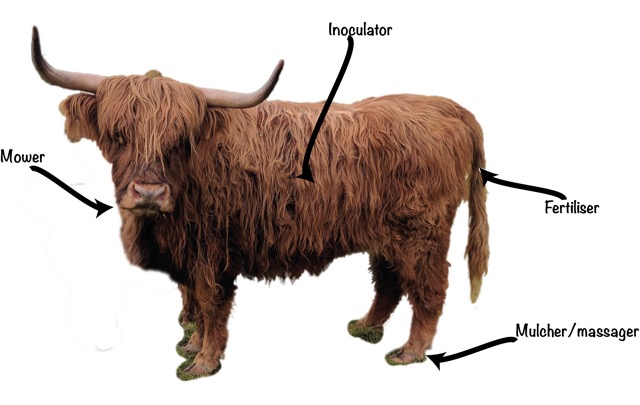

In the other, Savory, Massy and Fuhrer described how properly managed high-density holistic-grazed animals effectively stimulate soil recovery and plant growth. This grazing system aims to mimic the large herbivore migrations that (used to) occur in the wild. When ruminants are grazed in this manner, their dung and urine provide both water and a naturally balanced fertiliser. Furthermore, as the animals are rapidly moved from one area to the next, they graze only the tips of the plant. This ensures that most of the root structure remains intact which then enables the plants to recover swiftly. In addition, their hooves act as mulching machines that trample a large proportion of the plant onto the ground which provides both additional protection and nutrition for the soil.

If those benefits weren’t enough, their rumen microbial content, which is highly similar to the microbial soil population, also inoculates the soil. This is especially important after a dry period as it can ‘kick-start’ the natural soil ecosystem. Using high-density grazing, rapid stock moves combined with long rest periods after grazing, there is a tipping point where the population density of soil microbes and plants becomes sufficiently high that they switch on different sets of genes. This quorum sensing triggers rapid soil-building and increases in soil carbon. The results can be truly staggering.

As the general public’s shouts to mitigate climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution get louder, a saying from Spiderman always springs to my mind “With great power comes great responsibility.” I think (hope) there is a new age of farming dawning – one that works with Nature to solve these problems while at the same time still manages to provide a growing population with diverse, high quality, nutritious food. Groundswell 2019 showed farmers and policy makers that this is highly feasible and can also be profitable. Roll on Groundswell 2020.

Pen Rashbass is a volunteer copywriter for Agricology.

View video footage recorded at Groundswell 2019 here.

All photos and images taken / created by Pen Rashbass.